Riggs, William E.

- Service Branch: US Army

- Rank or Rate: Sergeant

- Service Dates: 1942-1945

- Theater: Europe

When Bill Riggs graduated from high school in Grimesland, NC in 1939, he had no money, no job, and little idea of what he would do as his life’s work. The intervention of World War II gave Riggs strong direction to his life and resulted in significant accomplishments during his careers in both civilian and military work.

When Bill Riggs graduated from high school in Grimesland, NC in 1939, he had no money, no job, and little idea of what he would do as his life’s work. The intervention of World War II gave Riggs strong direction to his life and resulted in significant accomplishments during his careers in both civilian and military work.

To Riggs, as for most high school graduates in 1939, the war in Europe was far away and not an immediate concern. His main concern was getting a job and upon the advice of his sister, went to Business College in Fayetteville, NC for a one-year course of study. Upon graduation, he went to work for the Civil Service at Ft. Bragg for a time.

On December 7, 1941, Riggs and some friends were riding in a car and listening to the radio. They heard the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor and unlike most young people, Riggs was a student of history and current events, and he understood better than most what this meant for our country.

As required, Riggs promptly registered for the draft. His superior at Ft. Bragg told Riggs he thought a deferment from military service might be possible due to the nature of his work at Ft. Bragg, but Riggs was not interested in deferment and indicated he would let events take their course. That decision resulted in his being drafted in November 1942. He had seven days to get his affairs in order and could only bring the clothes he was wearing to Ft. Bragg where he was inducted. He was told his civilian clothes would be shipped back home. He never saw the clothes again.

Riggs left Ft. Bragg for Camp Claiborne, LA after five days of getting uniforms, shots, KP duty, as well as limited indoctrination to the US Army. His trip to Camp Claiborne was on a crowded troop train. The trip started with lunch, and a fellow soldier spilled a full cup of hot coffee on Riggs’ new olive drab trousers. The sharp crease in his trousers was gone!

The 103rd Infantry Division was formed at Camp Claiborne and Riggs was asked his preference for duty. Having only his experience in Civil Service at Ft. Bragg in Ordnance, he chose Ordnance with the 103rd Infantry Division. His basic training was at Camp Claiborne. The only wound Riggs received during WWII was there during a demonstration where dynamite caps were used. One of the caps exploded at a distance from him during the demonstration and Riggs immediately felt a shock and blood running down his hand. A portion of the exploded dynamite cap had imbedded itself in his hand. The surgeon at the hospital could never find it and today that little piece of metal sometimes bothers Riggs.

One day, a notice on the bulletin board appeared asking for volunteers for Army Air Corps pilot training. Riggs volunteered along with a few friends. In September of 1943, Riggs received orders to Keesler Field, Biloxi, MS to begin the pilot training process. Riggs recalls one test called the sweaty palms test. If your palms were sweaty when you shook hands with the examining doctors, you were dropped from the program. The theory being, if you could not take the stress of an Air Corps physical without sweaty palms you could not take the stress of piloting an airplane. This was great duty for 5 months until the news was published that the air war in Europe was going so well that additional pilots were not needed. His pilot training ended.

Riggs was eventually sent back to the 103rd Infantry Division, now in Houston Texas. Back to the same typewriter he had used and with the people he had left some months before. This time however, the 103rd was headed for Europe. In October 1944, Riggs’ division was loaded on a converted Italian luxury liner bound for Marseilles, France.

Sixteen days before the ship arrived, the German army had been driven from Marseilles, so the city and port were bombed out and it was an awful scene to Riggs. During the two weeks Riggs was in Marseilles, trucks and jeeps were being unloaded from the ships in boxes. They had to be put together like an assembly line. Typical of an assembly line, when work was finished on a vehicle, a driver jumped into the vehicle and drove it off to the waiting army unit for whom it was destined. After all the 103rd units were delivered, Riggs asked for, and received, one more Jeep – unauthorized but delivered nevertheless – and it allowed Riggs as the driver, and his commanding officer, to ride over 10,000 miles in Europe with their own private transportation accommodations.

As the 103rd advanced in late 1944 on the same path the retreating German army took, the carnage of war was evident everywhere. Dead soldiers, dead horses, and burned-out vehicles lined the roads. In mid-December 1944, with the war seemingly winding down, heavy snow started falling and the 103rd pulled back for a time to watch for any action by the Germans. At this time the Battle of the Bulge started. At 4 a.m., the division was notified to leave in one hour, heading toward the raging battle to take up position in the area the 101st airborne division had vacated when they went to Bastogne. Every day and night, the battle sounds could be heard. Snow was 48 inches deep in many places and movement was almost impossible. Each night Riggs was responsible for typing up the day’s activity report and hand delivering it to headquarters. The first night he delivered the report, Riggs ran into a German roadblock but there were no German defenders. Then he saw two dead German soldiers, which were all that remained of the defenders of the roadblock.

Riggs spent many months going across Germany, to Darmstadt, Ulm, Heidelberg, and Nuremberg among many cities. Visiting the stadium in Nuremberg where Hitler had made so many political speeches was a sobering experience to Riggs, and the vision of that stadium lives in his memory. By April of 1945, the German army was in fast retreat. It was necessary to find gasoline for Patton’s tanks as they were advancing so fast that gas was in short supply. Riggs accompanied his superior officer on a mission to find gasoline wherever they could. In coming into a small town in Germany, they noticed several German soldiers with a crowd of persons going into a church service. This happened to be in front of the mayor’s office and Riggs’s superior told the mayor to tell the soldiers to turn in their arms and surrender to the two of them. There were 32 soldiers and they all surrendered and walked behind Riggs’s jeep back to the main lines as prisoners. Riggs and his superior went back and found 14 more German soldiers, who became their prisoners. Riggs still perspires when he thinks of the audacity of, he and his superior officer rounding up 46 armed German soldiers as prisoners, having only a rifle and a pistol as weapons to use if they had to do so.

Riggs was in Innsbruck, Austria when the war ended. He and others collected arms from the Germans still standing guard. They were very docile and offered no resistance. He sent a copy of the Star and Stripes newspaper to his sister showing the headline of the war being over and he received this treasured paper back from his sister’s family 50 years later.

Riggs had sufficient points to get out of the service so was ordered to Camp Lucky Strike for processing to return to the United States. He went to the United States by ship in July 1945, landing in New York. He received 30 days leave, which he spent in Grimesland, NC, and Tulsa, OK. In September 1945, he went to Fort Campbell KY and was discharged on Thanksgiving Day from Fort Campbell.

Riggs attended NC State on the GI Bill, majoring in Textile Engineering. A major part of his career, however, was spent as a Division Manager for Chase Packaging in Reidsville, NC.

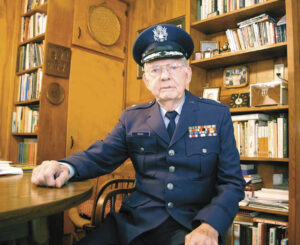

Riggs had joined the ROTC at NC State and in 1947, when an Air Force unit was formed immediately after the establishment of the Air Force as a separate branch of service; he transferred to the Air Force ROTC. That was a good move as in his succeeding years in the Air Force Reserve, Riggs advanced to the point where he was appointed by Governor James Hunt as Assistant Adjutant General for Air with the rank of Brigadier General.

Riggs was married to Rebecca, now deceased, for 54 years and has 3 daughters, one deceased, and 7 grandchildren.

Riggs says his WWII experience was personally rewarding in many ways, but he would not want to repeat it. The changes it made in his life are profound. He also wonders if he would ever have left Black Jack, NC except for his participation in World War II.

Interviewed 11/17/1999