Atkinson, Walter Green Jr.

- Service Branch: US Army

- Rank or Rate: Major after WWII

- Service Dates: 1939-1961

- Theater: Europe

During the June 6th D-Day landing at Utah Beach, Sergeant Walter Atkinson’s instructions were for his men to get off the beach and to the high ground, a series of sand dunes about 75 yards from the water’s edge. His first view of the beach as the heavy steel door slammed down in the water was of German machine guns firing at his landing craft. The water was neck deep and it was 75 yards to the beach. How is it that Atkinson found himself in this precarious situation, taking part in the greatest invasion by sea in history?

During the June 6th D-Day landing at Utah Beach, Sergeant Walter Atkinson’s instructions were for his men to get off the beach and to the high ground, a series of sand dunes about 75 yards from the water’s edge. His first view of the beach as the heavy steel door slammed down in the water was of German machine guns firing at his landing craft. The water was neck deep and it was 75 yards to the beach. How is it that Atkinson found himself in this precarious situation, taking part in the greatest invasion by sea in history?

Atkinson had joined the US Army in September 1939 because he wanted to get a steady job and see the world. Little significant work was available in Leaksville NC for an 18 year old high school graduate. He was not well informed on the European situation nor did he care. An Army job and steady pay was of most importance. Atkinson’s father drove him to Danville and after a few days Atkinson was in the Army and bound for Panama, having been assigned to an Infantry Chemical Company specializing in the use of mortars in combat. Five weeks of intense basic training followed including the usual close order drill, calisthenics and classroom work. During the five weeks of basic training, he could not talk to anyone except his drill instructor. He was training 12 hours per day with homework at night. “Rigorous” is the word for it according to Atkinson.

After five weeks he was integrated into the mortar company and promoted to Private First Class. He was assigned as a “saddler” responsible for repairing harnesses and saddles for the officers. The Army used horses and mules largely to move men and material. There were only 160,000 men in the peacetime Army and money for mechanized equipment was scarce. That changed immediately upon the entry of the United States into WWII in December 1941.

Atkinson was a very good baseball player. Sports competition was intense in those peacetime Army days, so his talent helped him to be promoted to Specialist 4th class at the rate of $45 per month. A private only made $21 per month. He lived well and worked half a day as a saddler and the rest of the time played baseball for the base team. This was his job for two- and one-half years in Panama. He considered himself well off for a young single man his age.

The war was heating up in Europe and the Far East and there were frequent briefings to the men on the news. No radios were available to the men on the base. When the attack on Pearl Harbor was announced, Atkinson and his friends were on the porch of his barracks. The full implications of the attack did not register on the men until later in the day when the complete report was in the newspaper.

The immediate orders to Atkinson and his fellow soldiers were to pack up, go into the jungle and take up pre planned gun positions to guard the Panama Canal as it was a prime enemy target. They stayed in the jungle for ten days. It was boring, lonely work. The food available was pork and beans, canned tomatoes and whatever game could be shot and cooked. The routine was; after ten days, his unit came back to the base to help train draftees and in another ten days back to the gun positions guarding the Canal.

In late 1942, his unit was split up into teams and was assigned to New Orleans to train draftees as part of formal basic training which the Army instituted at that time. Meanwhile, Atkinson had been promoted to Tech Sergeant and was now making $95 per month. In early 1943 he was sent to Fort Rucker Alabama to help form and train mortar companies for combat assignment. It was there the 87th Chemical Mortar Battalion was formed, using the 4.2 inch diameter mortar.

Atkinson spent the balance of 1943 and into 1944 in training mortar men. In April 1944 the 87th Mortar Battalion was sent to Tivington, England in preparation for the invasion of France.

In England the buildup for invasion was overwhelming with soldiers and equipment everywhere. It was clear to Atkinson that the invasion had to happen soon. Every day his unit engaged in mock battles and other training to the point where he was prepared for just about anything that could happen.

On June 3rd the men went aboard their mother ship as though it were just another practice landing. The weather was terrible, and the men were seasick. On June 5th at 4:30 AM the men were told the invasion was scheduled for that day, but the weather was too severe and the landing had to be postponed to June 6th. On the evening of June 5th the men were very edgy. They talked with each other, mostly about home and family. Atkinson said “We were fearful because we knew the Germans would throw all they had at us. We were so physically sick we wanted to get off that boat and get the invasion over with.” In spite of poor conditions, morale was high.

Early on June 6th, Atkinson and his men got up for breakfast after a mostly sleepless night. They were given anything they wanted to eat but many of the men were so sick they could not eat. General Kermit Roosevelt, the son of President Teddy Roosevelt, was on board Atkinson’s vessel and was very visible, encouraging and being supportive to the men. Even though the weather was better that day, there were still 20 foot waves and loading the LCVPs (Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel) with men, mortars and ammunition was very treacherous. It was extremely difficult to go down the netting hanging over the ship’s side. Some men fell while boarding their LCVPs and broke their legs, arms or backs.

The noise from naval bombardment, wave action, fumes from the engines and thoughts of the dreaded invasion were overpowering. All of Atkinson’s thirteen men threw up their breakfast. The men hunkered down in the LCVP on each other’s backs behind the big steel door which would drop and allow them to go on their way to shore. They circled the mother ship several times waiting their turn to advance to shore. There were about 100 LCVPs going ashore on that 7th wave of attack. When their time came, the landing craft hit the beach, the big door crashed open downward, and all the men were exposed to machine gun fire as they left the landing craft. The water was neck deep, but no one drowned in Atkinson’s group. Two men were hit by machine gun fire, and they were left on the beach for the medics to care for as there was nothing Atkinson’s men could do. They died. Many men were dead floating in the water with their life vests on, but Atkinson and his men did not focus on them but rather on their mission to get on the higher ground. There were many large steel cross obstacles which made progress difficult for vehicles and tanks.

Atkinson’s orders were to get to the higher ground about 75 yards from the water’s edge. From there he and his men were to fight their way to the nearby town of Saint Mere Eglise, link up with Airborne troops dropped earlier that morning and continue on to capture the port city of Cherbourg.

As history tells us, the battles took much longer than the best planning had projected. Day by day Atkinson and his mortars advanced toward St Mere Eglise. It took four days instead of one day to reach there and much longer to capture the port city of Cherbourg. Atkinson acted as forward observer in many cases so was very close to the enemy as mortar shells fell on them. On the fourth day in action Atkinson was wounded in the knee by an artillery shell. He was taught to dress himself, if possible, which he did. He took morphine to ease the pain and stuck his rifle in the ground so a medic would see it. He was picked up by a medic and evacuated to a hospital ship for transfer back to England and treatment. After 30 days of healing and rehabilitation he was sent back to his unit.

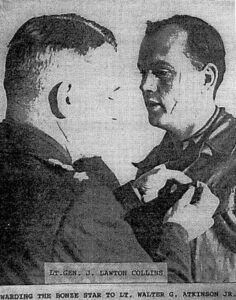

He came back as platoon leader and led his men until he received a battlefield promotion to reserve 2nd Lieutenant at Liege, Belgium. He was then put in charge of two platoons: about 60 men. A few days after his promotion Atkinson was slightly wounded in the head by a sniper’s bullet that would have killed him except for the protection of his helmet. At Malmody, Belgium his unit was cut off and surrounded by German troops, but the Germans went around rather than capture the surrounded troops. German forces were taking no prisoners at this point in the war so Atkinson said his unit would have fought to the death if necessary. Atkinson was involved in many major battles as he and his unit fought across France and into Germany. While on a 21 day leave in Leaksville, he learned about the German surrender. His unit was then sent back to the US for more training in anticipation of the invasion of Japan. While in training, the war with Japan ended. He was sent to Fort Benning GA and was asked to decide whether he wanted to stay in the service or get out. He became a civilian for eight months and then decided to go back in the Army at his permanent rank of Sergeant. During the Korean War he asked to be “recalled” as a reserve officer which he had been during WWII after his battlefield promotion. This was technical and gave Atkinson his commission back which he retained for the rest of his 21-year military career. Atkinson says his experience in Korea was worse than his WWII experience but that will have to be told in another story.

Atkinson retired from the Army in 1961, came back to Leaksville and was in various businesses, the last being vice president of Stoneville Furniture Company until his full retirement in 1988.

He is married to his wife, Nadine and lives in Leakesville. He has two sons, one of whom is deceased and one daughter. He says his experience in WWII of hardship, discomfort and fear was like many other combat veterans and he was proud to serve. He met some of the bravest men he ever knew while in combat. If he had to do it all over again for his country, he would.

Interviewed 2/24/2004