Shinn, Conrad “Gus”

- Service Branch: US Navy

- Rank or Rate: Lt. Commander

- Service Dates: 1942-1963

- Theater: Pacific/US

Mount Shinn is the third highest mountain in Antarctica at 15,292 feet. It is named after Conrad “Gus” Shinn from Spray NC, the first aviator to land an aircraft on the South Pole, in connection with Operation Deep Freeze II, an Antarctic Expedition in 1956.

Mount Shinn is the third highest mountain in Antarctica at 15,292 feet. It is named after Conrad “Gus” Shinn from Spray NC, the first aviator to land an aircraft on the South Pole, in connection with Operation Deep Freeze II, an Antarctic Expedition in 1956.

Some of Gus Shinn’s earliest memories are of his father’s World War I uniform, and other accessories kept in a trunk in the attic. Shinn was intrigued as his father talked of combat and the aviators with their heroics in WW I. As a youngster, Shinn would dress up in his father’s uniform, put on the gas mask and play soldier. His father and mother were always a great inspiration to him and the early exposure to things military later guided Shinn to a career as an aviator in the US Navy.

During his growing up years and into high school, Shinn followed current events and was aware of the history unfolding in Europe in the late 1930s. After graduation from Leaksville high school, Shinn entered NC State to study aeronautical engineering and felt a natural inclination to join the Reserve Officers Training Corps.

In 1942, at the end of his 3rd year at NC State, Shinn elected to join, and was accepted in, the US Navy aviation cadet program. Pre-flight training was at University of North Carolina followed by primary training at Naval Air Station (NAS) Olathe KS and advanced training at NAS Corpus Christi TX. Shinn wanted to be a multi engine pilot and it was helpful that single engine (fighter aircraft) and multi engine (transport aircraft) pilots were separated into their categories alphabetically. Shinn’s name being near the end of the alphabet put him on the multi engine path.

Shinn was commissioned an Ensign and received his “gold wings” as a naval aviator in August 1943. He went on to advanced instrument school in late 1943 and in early 1944 was assigned to VR-1 (transport squadron 1). For about six months, he was flying high priority equipment in the anti-submarine effort to east coast destinations. Shinn was transferred to the South Pacific in late 1944.

Shinn explains, “Flying in combat conditions in the South Pacific was an extreme challenge, continually flying beyond our capabilities in all kinds of weather. We were just plain lucky we did not get killed.” Shinn would fly onto an island, which was not secured yet by our forces, to deliver whole blood, and on the return, take wounded soldiers back for medical care. The lumbering R5Ds (larger transport aircraft) made tempting targets for Japanese sharpshooters. It was common to have bullet holes in the fuselage of the aircraft after one of those missions. Coming into Okinawa on one such mission, Shinn could see US Navy ships firing their big guns and Japanese kamikaze (suicide) aircraft targeting our ships – with some success. One wounded soldier being evacuated for medical care by Shinn said, “I feel safer in my foxhole than in your plane.”

Shinn was on a flying mission when he heard news of the Japanese surrender – VJ Day (victory over Japan). A Happy Day!

For six months after VJ Day, Shinn was stationed on Guam, assigned to a medical evacuation squadron flying former US prisoners of war back to the states. When that assignment was completed, Shinn was sent back to his old squadron, VR-1 at Anacostia Naval Air station in Washington DC. He was contacted by Trigger Hawkes, a friend from South Pacific days who asked Shinn if he would like to go to Antarctica with the famous Admiral Byrd as part of a secret operation – Operation High Jump. It is said the reason for Operation High Jump was to help prepare the US Navy to fight the Russians in polar conditions. Shinn enthusiastically agreed.

Operation High Jump lasted from September 1946 to May of 1947, but only 30 days were spent at Little America in Antarctica. The participants went to within 400 miles of Antarctica on the aircraft carrier Philippine Sea with six R4Ds (smaller transport aircraft) aboard. Shinn’s plane and the others flew from the deck, and it was the first time aircraft of that size had taken off from an aircraft carrier. Colonel Doolittle’s B-25 bombers, which took off from the aircraft carrier Hornet on the Tokyo raid in 1942, were smaller but heavier.

The R4Ds were also fitted with skis for snow landings, which barely allowed the wheels to protrude and roll on the deck. Shinn was the person who tested the skis and found them satisfactory for use in Operation High Jump.

Shinn’s R4D and the five others mapped about 200,000 square miles of Antarctica in 30 days. Shinn came to know Admiral Byrd well and was a great admirer of this world-famous explorer.

Shinn then returned to Washington DC to his old squadron – VR-1. In early 1949, Shinn was assigned for two years to London where he transported high profile military and civilian personnel.

From December 1951 to March 1955 Shinn was in advanced schools, flight operations at Pensacola FL and in helicopter pilot training. In March 1955, Shinn read a Navy release requesting volunteers for a new exploration initiative to Antarctica called Operation Deep Freeze. The challenge appealed to Shinn’s adventuresome spirit, and he volunteered to become part of the operation. Deep Freeze I called for the establishment of a permanent research station to support later Deep Freeze operations. The Navy’s part was to support US scientists for their part in later International Geophysical Year studies. Unfortunately, the R4Ds flown by Shinn and others did not have enough fuel to overcome the fierce winds so had to turn back. Timing issues prevented Shinn from taking any additional flights to Antarctica in Deep Freeze I. The goal of Deep Freeze II was to establish a permanent station at the South Pole.

The R4Ds had additional fuel tanks installed to give greater range. Shinn’s flight to McMurdo Sound, Antarctica was in October 1956. The weather was terrible. Shinn and his crew had on the survival suits in case they had to ditch in freezing water with 50-foot waves. Shinn knew he would die if that option came up, so tried not to think about it. Prior to Shinn’s arrival, another plane had crashed into a mountain, and everyone aboard was killed. Shinn’s first flight over Antarctica was almost a disaster. Shinn’s R4D was fitted with nineteen JATOs (jet assisted take off) attached to the fuselage, in case of trouble. Over the Executive Range of mountains, the aircraft was hit with a wind shear and airspeed dropped precipitously causing the plane to drop like a rock. A wing brushed the ground and threw up a cloud of ice crystals as Shinn fired all nineteen JATOs. The plane rose like a helicopter from this great driving force, averting disaster. Several planes were lost during the eight months duration of Deep Freeze II.

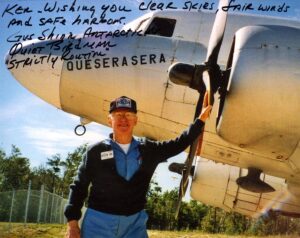

At about 3 a.m. on October 31, 1956, Admiral Dufek, the Commander of Deep Freeze, had Shinn and the crew of his aircraft; “Que Sera Sera” awakened and were told that the flight to the South Pole would take off in secret at 8 a.m. There was a bit of rivalry as to which person would land first at the South Pole, Admiral Dufek or veteran Antarctic explorer Paul Siple who had accompanied Admiral Byrd on his first expedition in 1927. Dufek won this contest.

Lights and shadows on the icy ground at South Pole made it difficult to be certain the landing was not to be in a crevasse. Shinn circled several times and finally felt comfortable enough with the lay of the land to come in safely. The passengers and Shinn left the aircraft with the engines idling, to avoid any possibility of the engines freezing at a temperature of 65 degrees below zero. All the instruments were sluggish and there was real danger of hydraulic fluid freezing which would prevent takeoff. In addition, the South Pole is at approximately 9,000 feet elevation, which adds to the difficulty of takeoff due to “thin air.”

After 45 minutes outside the aircraft, the group was ready to head back to McMurdo Sound. In preparation for takeoff, it was obvious the skis were frozen to the ground. Shinn gunned the engines, but the plane did not move. It took all 16 of his JATOs to move the lumbering aircraft into the freezing air. It was touch and go while the plane slowly gained altitude and then safely returned to McMurdo Sound. Conrad Shinn from Spray NC – the first pilot to land an aircraft at the South Pole! The best part is, Shinn was also the first to take off from the South Pole.

Shinn describes the South Pole as the most remote, windy, cold, desolate, rugged yet beautiful place on earth in his opinion. Temperatures range from 20 degrees below zero in “warm” weather to 126 degrees below zero in the coldest weather. Antarctica is one- and one-half times the size of the United States and has an 18,000 mile coastline..

Shinn remained in Antarctica for the remainder of the expedition carrying men and material for the permanent station at South Pole. He also returned the following year for Deep Freeze III doing similar work.

In mid-1958, Shinn was transferred to NAS Pensacola FL to a flight operations job, and he retired from his Navy career 4/1/1963. Shinn has remained in the Pensacola area and even now he will see Navy acquaintances browsing in the National Museum of Naval Aviation in Pensacola or visiting at restaurants and they will remember him and thank him for the leadership he displayed over the years, especially to younger aviators.

On November 10, 2006, the Museum celebrated the 50th anniversary of the South Pole landing and paid tribute to Shinn’s courage in accomplishing this aviation milestone. Shinn says he never thought about the danger. He said, “I was in the military and when our superior officer said go, we went.”