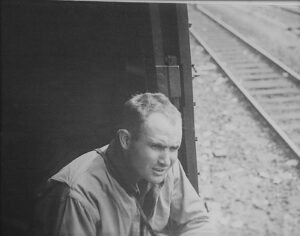

Bailey, Warren H.

- Service Branch: US Army

- Rank or Rate: Major after WWII

- Service Dates: 1943-1946

- Theater: Europe

During WWII, Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, Commander of the German Luftwaffe (air force) had a fetish of “collecting” homes, rare art, tapestries, and beautiful women. One of his hideaway castles was in Bruck, Austria. Warren Bailey was one of the soldiers that used the castle for living quarters while stationed in Bruck as part of the Army of Occupation. Lieutenant Bailey used the room that Hermann Goering had slept in from time to time. He possesses to this day some dishes he “liberated” from Goering’s castle and brought home in 1946.

During WWII, Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, Commander of the German Luftwaffe (air force) had a fetish of “collecting” homes, rare art, tapestries, and beautiful women. One of his hideaway castles was in Bruck, Austria. Warren Bailey was one of the soldiers that used the castle for living quarters while stationed in Bruck as part of the Army of Occupation. Lieutenant Bailey used the room that Hermann Goering had slept in from time to time. He possesses to this day some dishes he “liberated” from Goering’s castle and brought home in 1946.

Warren Bailey was raised in the small town of Carpenter, NC and attended a three-room schoolhouse. He later attended Apex High School and after graduation in 1939 attended NC State, studying Agronomy. While at NC State he joined the ROTC. War news was well disseminated to the ROTC unit and Bailey was aware of the seriousness and the implications of the Pearl Harbor attack to him personally. During his junior year, with thirty days’ notice, his ROTC unit was activated April 6, 1943. He entered the Army at Fort Bragg where he received his obligatory crew cut, uniforms, and shots. From there, he went to Camp Wheeler, Georgia for four months of basic training. Due to lack of openings in Officer Candidate School, he was assigned back to NC State for additional training. In February 1944, he was assigned to Fort Benning, GA to OCS. Before leaving for OCS, Bailey married Ruth, the young woman he had fallen in love with several months earlier. Ruth Bailey accompanied him to Ft. Benning, living off base in an apartment but he could only see her on weekends.

After graduation and a brief period at Camp Butner, he was given a four-month assignment to Fort Benning for communication training. There he learned the three basic methods of battlefield communication: 1) wire telephone, 2) message Center – radio communication using secret cryptography, and 3) radio, using Morse code.

Upon rejoining his outfit at Butner, the battalion was assigned in December of 1944 to Camp Miles Standish near Boston. While at Camp Miles Standish, Bailey had his most unpleasant duty to date in the military – censoring mail. It was difficult to read letters home to sweethearts, wives, and children telling of the men’s fears in going into combat and then cutting out with a razor blade any reference to something that was prohibited.

In late December 1944, Bailey and his battalion left for Southampton, England on the military transport Marine Wolf. Bailey was so seasick that he slept on deck most of the trip. The Battle of the Bulge was going badly at that time so the ship was rerouted to Le Havre, France so the battalion could get into action earlier.

Bailey describes his job as communication officer as being responsible for setting up communication between Battalion headquarters to the three or four companies making up a battalion. Typically, Battalion HQ was about one mile behind the company. It was imperative that the wire for telephone communication be strung and intact every night so planning could be coordinated.

Usually, Bailey’s unit only received one- and one-half mile of wire per day. It was common to reuse wire that had been previously used by German communication units. In addition, Bailey sometimes used lines that were in place on civilian telephone poles. In combat, troops were advancing so fast that wire recently laid had to be retrieved using a Jeep with a reel device on the front, which was wound by hand. It was back breaking work to wind up telephone wire only to lay it again quickly. Night was the most dangerous time to be laying wire. It was then that maps could be most easily misinterpreted. To check a map at night, Bailey would have to get under a raincoat and use a flashlight, determining where he was going. Any light shown was an invitation for rifle fire from the Germans. Many times captured German maps were the only maps available. When the unit to which the wire was being laid was approached, it was necessary to be recognized and give a sign such as “HAM” with a countersign response from the other soldier such as “EGGS”. Failure to give a sign or counter sign properly could result in death to the one who “forgot”. New signs and counter signs were given each day. German soldiers were sometimes dressed as American soldiers, so knowledge of signs and counter signs was extremely important to avoid being shot by “friendly” forces.

Near the city of Le Treporte France, Bailey, and his unit came upon a 12-year-old French girl who was friendly and gave the men some food as well as a picture of herself with her name on back of it to Bailey, who sent it on to his wife. In 1993 on a trip to France, Bailey was determined to find the girl, then about 62 years old. With a stroke of luck, he did so and had a nice reunion with her after 49 years.

About this time, Major James Morris was appointed the new battalion commander. Because Morris was an outstanding leader, Bailey credits Morris with saving his life and many others. The first real combat assignment after a minor skirmish at Triere was the assault to cross the Mozelle River. There was not much opposition at the time Bailey’s unit crossed the river. However, the process of laying communication wire did expose him and his men to enemy fire.

The crossing of the Rhine eleven days later was a different story. Opposition was fierce with the Germans firing machine guns as well as using their 88 mm guns with high fragmentation anti-aircraft shells as an artillery barrage. The projectiles made a frightening whirring sound, and many soldiers were killed by shrapnel. Bailey was in a foxhole before making the assault but saw Major Morris up and about, ignoring the rifle and machine gun fire, encouraging his men. Bailey got out and did the same with his platoon of 30 men. Battalion Commander Morris was a great example to many young men under terrifying circumstances and Bailey did his best to emulate him. As the assault was being made over the Rhine, Bailey’s unit strung communication wire with all the shelling and confusion going on.

After the Rhine was bridged and the tanks moved across, Bailey’s battalion raced deeper into Germany. The town of Eisenach was bypassed on the way. Later, a US officer raised a white flag to approach the surrounded German position and asked them to surrender to avoid an attack that would destroy them and the town. The German general in charge told our officer that he was under orders not to surrender. The town was destroyed that evening with an 1800 artillery shell barrage. When Bailey and other soldiers entered Eisenach the next day, there was no opposition.

When Bailey’s unit approached the village of Ohrdruf, not too far away from Eisenach, a scout unit saw several large low buildings and many dead bodies and skeleton-like figures moving about. It was the Ohrdruf work camp which was the first nazi “concentration” camp liberated during the war and this is substantiated by the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC. It did not get much attention at the time, as President Roosevelt died the day it was liberated.

The war was just about over and Bailey’s unit camped near Leipzig as it was agreed by the allied powers that the Russians were to enter Berlin first. Bailey’s unit waited and waited. About that time, Bailey was granted some R&R (rest and recreation) time in Paris. While he was there, the Germans surrendered. It was the first time in five years the lights were on at night in Paris. Bailey said he had to get out of downtown Paris as the noise and general bedlam was overwhelming. The next day a pilot flew a small observation plane under the Arc de Triumph in celebration of the allied victory.

Bailey went back to his unit, and it was ironic that when he had left his unit, US troops were shooting at the Germans and them at us but now German soldiers were just abject bedraggled old men and very young boys who were prisoners and marching to their prison camps for further processing.

Bailey was transferred to Camp Lucky Strike to help reassign soldiers to Japan, return to the US or just get out of the service if they had enough points. He was there until the atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. He was in London on a brief leave when victory was declared over Japan. The streets were full of people celebrating after almost six long years of war.

Bailey went back to his unit as part of the Army of Occupation managing a relocation camp for displaced persons in Bruck, Germany. He lived in former Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering’s “castle” while in Bruck. His job was to help direct displaced people to their destination or reunite them with family. In early 1946 while in Austria, Bailey was a marshal supervising a group of military policemen at a war crimes trial of Hungarian SS officers who killed five American flyers. Recently, through help given by Holocaust Museum personnel in Washington DC he found the June 9, 1946, N.Y. Times article telling the final results of the trial he observed for a time in 1946.

In June 1946, Bailey was transferred to Camp Kilmer NJ and took a train to Fort Bragg for release from active duty. His wife Ruth picked him up and he met son William whom he had never seen. He returned to NC State and went on in his career to become manager of several Agricultural Research Stations in NC. His final position was in Rockingham County as Agricultural Extension Agent.

Bailey is married to wife Ruth and has two sons. One son is William, a ten-year Air Force veteran with the rank of Captain, now retired and living in Chapel Hill. The second son is Daniel; a Reidsville attorney and Army veteran associated for three years with the Judge Advocate General’s office in Washington DC while on active duty and a retired Lieutenant Colonel in the National Guard after 20 years’ service.

Bailey said he was happy and proud to help in the effort to defeat fascism and because of the war, he met his wife, which changed his life in a wonderful way.

Interviewed 12/28/2001